Think of the statute of limitations on debt as a legal expiration date. It’s a state law that puts a strict time limit on a creditor’s right to sue you over an unpaid debt. Once that clock runs out—usually after 3 to 6 years—the debt becomes “time-barred.”

While the debt doesn’t magically disappear, the creditor loses their biggest stick: the power to take you to court. This means any lawsuit they file against you is legally out of bounds.

Your First Line of Debt Defense

Imagine a stopwatch starts ticking the moment you default on a payment. That’s essentially what the statute of limitations is. It’s a fundamental consumer protection that prevents you from being ambushed by a lawsuit for a very old debt.

This concept is the bedrock of any solid debt defense. It forces creditors to act while the evidence—like statements and payment records—is still fresh and accessible. Without it, you could be sued for a credit card bill from 20 years ago, making it nearly impossible to find the paperwork to defend yourself.

How Statutes Protect Consumer Rights

Knowing your rights under the statute of limitations is crucial because it ties directly into federal law. The Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA) makes it flat-out illegal for a debt collector to sue you, or even threaten to sue you, for a debt that’s past this deadline.

When a collector tries to drag a time-barred debt into court, they’re breaking the law. Armed with this knowledge, you can spot these illegal pressure tactics and shut them down.

A key takeaway is that the statute of limitations is not just a technicality; it is a powerful shield. Knowing the specific deadline for your debt in your state gives you the leverage to stop aggressive and unlawful collection efforts.

Why State Laws Matter Most

There’s no single, nationwide statute of limitations for consumer debt. This is incredibly important to understand. Each state has its own set of rules, and the timelines can be wildly different. For example, the window to sue for credit card debt might be three years in one state but a full decade in another.

These differences highlight why you have to focus on your local laws. Broad economic data, like reports from the Institute of International Finance, can give you the big picture, but it’s the state-level rules that will make or break your case.

This is why the first step in any debt defense strategy is to learn the laws where you live. Knowing the rules of the game is the only way to protect yourself. To learn more about this, check out our guide on the effects of aging debt.

When Does the Clock Start Ticking? And What Makes It Reset?

To understand how the statute of limitations works, you first need to know when the legal stopwatch actually starts. It’s not as simple as the date you opened the account. For most debts, like credit cards or personal loans, the clock starts ticking from the date of your last payment or the date the account first became delinquent, whichever is more recent.

Think of it as the “date of last activity.” As long as you’re making payments, the account is in good standing and there’s no countdown. But the moment you miss a payment and don’t catch up, that’s when the timer begins for the creditor to sue you.

Don’t Wake a Sleeping Giant: How the Clock Resets

This next part is absolutely critical, and it’s where many people unintentionally get into hot water. Certain actions you take can completely reset the statute of limitations clock, bringing an old, legally uncollectible debt roaring back to life.

Debt collectors are experts at this. Their main goal with an old debt is often to coax you into doing something—anything—that restarts that timer. They know that if they can get you to make a tiny payment on a debt that’s five years old, the clock could reset to zero, giving them a whole new window to take you to court.

Be on guard for these common clock-resetting traps:

- Making a payment of any amount. This is the big one. Paying even $5 on a time-barred debt can be seen as reaffirming the entire amount you owe, resetting the clock in most states.

- Agreeing to a new payment plan. Whether you agree over the phone or sign a new document, setting up a payment schedule is a powerful way to restart the statute of limitations.

- Making a charge on an old account. If it’s an open account like a credit card, using it again will absolutely reset the timeline.

- Acknowledging the debt is yours in writing. Sending an email that says, “I know I owe this, and I’ll pay you when I can,” is a written admission that can be used against you.

It’s a tough pill to swallow, but your good intentions can be weaponized. A collector might say, “Just pay $20 to show you’re serious.” They aren’t trying to be helpful; they’re trying to get you to make a move that erases the legal protection the statute of limitations gave you.

How to Protect Yourself When a Collector Calls

So, what’s the right move when you get a call about a debt you don’t recognize or know is ancient? Your entire goal is to protect your rights without accidentally resetting that clock. The law is on your side here; the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA) gives you the right to request proof of a debt, and doing so does not restart the clock.

The words you use are incredibly important. You must not, under any circumstances, admit the debt is yours or promise to pay it.

Here’s a script for handling the conversation safely:

- Never claim the debt. Avoid phrases like “my bill,” “the money I owe,” or “my account with X.”

- State your request clearly and firmly. A good line is, “I don’t have a record of this debt. Please send a debt validation letter to the address you have on file.”

- Get off the phone. Don’t get drawn into a conversation about your job, your finances, or why you can’t pay. Just make your request and end the call.

This simple approach shifts the legal burden squarely back onto the collector. They are now legally required to stop contacting you until they mail you written proof that the debt is valid and they have the right to collect it. Most importantly, you’ve protected yourself without waking that sleeping giant.

State Timelines for Different Types of Debt

The statute of limitations on debt isn’t a single, straightforward rule. Far from it. It’s a patchwork of state laws that can change dramatically based on where you live and, just as importantly, the kind of debt you have. A handshake deal has a much shorter legal shelf life than a formal, signed-and-sealed car loan.

This is a crucial detail. The timeline for a credit card debt might be three years in your state, while the limit for a written personal loan could be six. That’s why you can’t rely on generic advice you find online—you have to know the specific rules that apply to your situation.

The Four Main Categories of Consumer Debt

Most consumer debts fall into one of four buckets, and each one comes with its own typical time limit for a lawsuit.

- Oral Contracts: Think of this as a debt based on a verbal agreement. Since there’s no paper trail, these usually have the shortest statute of limitations, often just 2 to 3 years. It’s tough to prove the original terms, so states limit how long someone can wait to sue.

- Written Contracts: This is the big one, covering most loans where you signed a document laying out the terms. Things like personal loans, auto loans, and even some medical bills often fall into this category. The timelines here are usually longer, typically running from 3 to 6 years.

- Promissory Notes: This is a more formal type of written contract where you make a clear, unconditional promise to pay a specific amount of money. Mortgages and certain student loans are classic examples. Because of their formal nature, they can have even longer statutes of limitations, sometimes 6 years or more.

- Open-Ended Accounts: This mostly means revolving credit—credit cards and lines of credit are the best examples. You can borrow, pay it back, and borrow again up to a set limit. States have specific rules for these accounts, with the time limit to sue often falling between 3 and 6 years.

The key takeaway is that the “type” of debt isn’t just a label—it’s a legal classification that dictates how long a creditor has to sue you. An old credit card bill and a forgotten medical debt from the same year could have completely different legal expiration dates.

Be careful not to restart the clock on an old debt. Certain actions can give a creditor a fresh timeline to sue you, even if the original one was about to expire.

As this shows, making even a small payment, promising to pay, or sometimes just acknowledging you owe the money can be enough to reset the statute of limitations, giving the collector a brand-new window to take you to court.

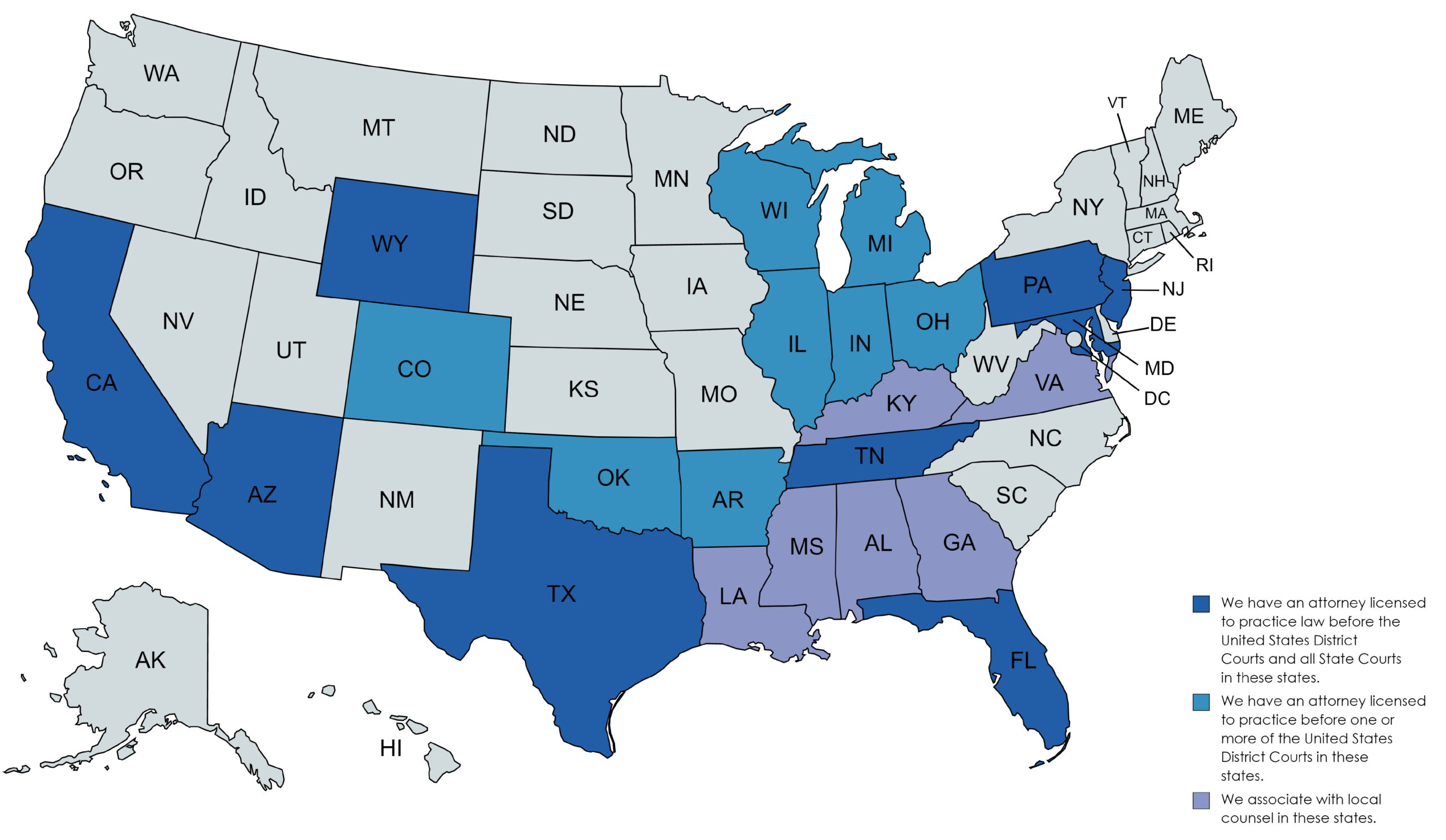

Comparing State Laws: A Quick Look

To see just how much these time limits can differ, you only have to look at a few states side-by-side. The table below makes it crystal clear why a one-size-fits-all approach to handling old debt is a recipe for disaster.

Statute of Limitations by State and Debt Type (Examples)

This table shows the different time limits (in years) creditors have to sue for various types of consumer debt in select states, highlighting the importance of state-specific laws.

| State | Oral Contracts | Written Contracts | Promissory Notes | Open-Ended Accounts (Credit Cards) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| California | 2 years | 4 years | 4 years | 4 years |

| Texas | 4 years | 4 years | 4 years | 4 years |

| New York | 3 years | 3 years | 3 years | 3 years |

This table provides general examples and should not be considered legal advice. State laws are complex and can change.

The differences are stark. In California, the limit for most written debts is four years, as laid out in the California Code of Civil Procedure § 337. But in New York, a recent change in the law shortened the period to just three years for most consumer debts. Meanwhile, Texas keeps it consistent with a four-year limit across these common debt types.

This is precisely why knowing your local rules is so critical. If a debt collector calls you about a five-year-old credit card debt in New York, a lawsuit would likely get thrown out of court as time-barred. But if you were in a state with a six-year limit, their case would still be perfectly valid. Your rights—and your defense—hinge entirely on these local timelines.

Understanding Time-Barred Debt and Your Rights

So what happens when that legal stopwatch on a debt finally runs out? The debt doesn’t just disappear into thin air. Instead, it gets a new name: time-barred debt. This is a huge deal, because it completely changes the game and puts much of the power back in your hands.

Think of it this way: the debt technically still exists on some company’s books, but the creditor has lost their most powerful tool for collecting it. Their window to file a lawsuit against you has slammed shut.

But just because they can’t sue you doesn’t mean they won’t try to get you to pay. This is where knowing your rights is your best defense.

Your Protections Under the FDCPA

The Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA) is a federal law that acts as a shield, protecting you from abusive, deceptive, or unfair collection tactics. When it comes to time-barred debt, the FDCPA is not vague—it’s direct and powerful.

Under the FDCPA, it is illegal for a debt collector to sue you or even threaten to sue you over a debt that’s past the statute of limitations. This isn’t a legal gray area; it’s a clear violation of federal law, and collectors can face serious penalties for it.

This single protection is your most important defense against collectors trying to resurrect old, “zombie” debts. They are often banking on the hope that you don’t know the law.

Spotting Illegal Threats and Intimidation

Collectors chasing time-barred debts have to be careful with their words, but many will still try to scare you into paying. Since they can’t legally say, “We will sue you,” they often resort to vague, intimidating language that hints at legal consequences.

Keep an ear out for shady phrases like these:

- “We will be forced to pursue other options.”

- “Our company will have to escalate this matter.”

- “We may need to take further action to resolve this.”

- “This is your final chance to avoid legal proceedings.”

Any statement that vaguely suggests a lawsuit, wage garnishment, or property lien is a major red flag and a likely FDCPA violation. These collectors are trying to intimidate you without explicitly crossing the legal line, but even these implied threats are illegal. To get a full picture of what collectors are and aren’t allowed to do, it helps to know your complete rights against debt collectors.

Lawsuit Deadlines vs. Credit Reporting Timelines

This is where things can get confusing. People often mix up the statute of limitations for a lawsuit with the timeline for credit reporting. It’s crucial to understand that these are two entirely separate clocks, and they almost never run for the same amount of time.

Imagine you have two different stopwatches. They both start at the same time, but they’re set to run for different durations.

- The Statute of Limitations Clock: This clock determines how long a creditor has to sue you. As we’ve covered, it’s set by state law and typically runs for 3 to 6 years. Once this clock runs out, the debt is time-barred.

- The Credit Reporting Clock: This clock is set by a federal law called the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA). It dictates that most negative items, like a delinquent account, can only stay on your credit report for seven years from the date you first missed a payment.

This is a critical distinction. A debt can become too old for a collector to sue you over, yet still be hurting your credit score. For example, if you live in a state with a four-year statute of limitations, a creditor loses their right to sue you after year four. However, that negative account can legally remain on your credit report for another three years.

Worse, if you acknowledge or make a payment on that debt, it won’t make it fall off your credit report any sooner, but it could reset the lawsuit clock, putting you right back in legal jeopardy.

Your Action Plan for Handling Old Debt Collectors

Knowing your rights is one thing, but what you do in the moment a collector calls is what truly matters. When it comes to old debts, one wrong move—even a single sentence—can reset the statute of limitations on debt, wiping out years of legal protection. Think of this as your playbook for navigating those tricky conversations, defending your rights, and sidestepping the common traps collectors lay.

Step 1: Master the First Contact

The second a debt collector contacts you about an old account—whether by phone, text, or email—your guard needs to be up. Your immediate goal is to gather information without giving any away. Above all else, you cannot acknowledge the debt is yours or make any kind of promise to pay.

Collectors are trained to coax you into admitting ownership. They use phrases like, “Let’s work together to resolve your account,” hoping for a simple “okay” that they can record and use against you.

Your response should be calm, firm, and completely non-committal. Stick to a simple script: “I don’t recognize this debt. You’ll need to send me a written validation notice to the address you have on file. I will not discuss this any further over the phone.” Then, hang up. This response doesn’t restart the clock, but it does trigger your rights under the FDCPA.

Step 2: Send a Written Debt Validation Letter

Following up that phone call with a formal, written debt validation letter is your most powerful move. Send it via certified mail with a return receipt requested. This legally requires the collector to stop all contact until they provide specific proof that you owe the debt and that they have the legal right to collect it.

This isn’t just a formality; it’s a critical legal step. A proper validation letter forces the collector to show their cards. For ancient debts that have been sold and resold, they often don’t have the original paperwork to prove their claim.

This letter puts the burden of proof squarely back on the collector. You aren’t disputing the debt; you are demanding they validate it. The distinction is crucial because demanding validation does not restart the statute of limitations.

Your letter should clearly state that you are not admitting the debt is yours. Use firm but neutral language. You can get a much better feel for how to do this by checking out our guide on how to use a debt validation letter template to dispute a debt. It’s an essential tool for protecting yourself without accidentally resetting the legal clock.

Step 3: Respond Immediately If You Are Sued

Ignoring a court summons is the absolute worst mistake you can make, even if you are 100% certain the debt is past the statute of limitations. If you don’t show up in court or file a formal answer to the lawsuit, the collector wins by default.

With a default judgment, the collector gets a whole new set of legal tools to use against you. They can potentially:

- Garnish your wages, taking money directly from your paycheck.

- Levy your bank accounts, freezing your cash.

- Place a lien on your property, making it difficult to sell or refinance.

The statute of limitations is what’s known as an affirmative defense. This means it’s on you to bring it up in court. The judge isn’t going to check the dates for you. You or your attorney must present it as the reason the lawsuit should be thrown out.

Step 4: Know When to Hire a Consumer Rights Attorney

While you can handle the first couple of steps on your own, some situations absolutely call for a professional. It’s time to hire a consumer rights attorney when:

- You receive a court summons. A lawyer will make sure your response is filed correctly and on time, properly raising the statute of limitations defense.

- A collector violates your FDCPA rights. If a collector threatens you over a time-barred debt, harasses you, or lies, you may be able to sue them for damages.

- The situation is complex. If you’ve moved between states with different laws, or if the debt is tied to something complicated like an estate, an attorney can cut through the confusion.

Facing down an illegal lawsuit from a debt collector is intimidating, but you don’t have to go it alone. A good debt defense lawyer can not only get the case dismissed but can also hold the collector accountable for breaking the law.

Common Questions on Debt Statutes of Limitations

Let’s be honest: navigating the rules around old debt can feel like walking through a legal minefield. The details often create more questions than answers. Here, I’ll clear up some of the most common and tricky situations you might encounter with the statute of limitations.

Can Old Debt Still Hurt My Credit Score?

Yes, absolutely. This is probably the biggest point of confusion when it comes to old debt. Think of it this way: there are two separate clocks ticking, and they are governed by different laws.

- The statute of limitations is a state-level law that dictates how long a creditor has to sue you. This period is usually somewhere between 3 and 6 years.

- The credit reporting period, on the other hand, is federal. The Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) says a negative item can generally stay on your credit report for seven years from when you first fell behind.

So, you could have a debt that is too old for a creditor to legally win a lawsuit over, but it can still be sitting on your credit report for a few more years, dragging down your score.

What Happens If I Move to a New State?

Moving across state lines really throws a wrench in things. You can’t just assume your new state’s rules apply. To deal with this, many states have what are called “borrowing statutes.”

Essentially, a borrowing statute instructs the court to use whichever statute of limitations is shorter—the one from your old state or the one from your new one. But there’s another catch: your original loan agreement might have a “choice of law” clause, which locks you into the laws of a specific state no matter where you move.

This is where it gets legally complex. You’re dealing with the interaction of two state laws plus the fine print of your original contract. Trying to sort this out on your own is a gamble. Your best bet is to talk to a consumer rights attorney to get a straight answer.

Restarting vs. Tolling the Clock: What’s the Difference?

These two terms sound similar, but they affect the statute of limitations in very different ways. Knowing the distinction is critical.

Imagine the statute of limitations is a stopwatch counting down the years.

- Restarting the clock is like hitting the reset button. The stopwatch goes right back to the beginning and starts a fresh countdown. Actions on your part, like making a small payment or admitting in writing that you owe the debt, are usually what trigger a reset.

- Tolling the clock is like hitting the pause button. The countdown stops for a period and then picks up right where it left off. This is usually caused by specific legal circumstances, like if you’re on active military duty, file for bankruptcy, or move out of the state for a while.

So if two years have passed on a four-year statute and you get deployed, the clock might be tolled (paused). When you return, the creditor would still have the remaining two years to file a suit.

Is It Illegal for a Collector to Contact Me About Time-Barred Debt?

Technically, no. It isn’t illegal for a collector to simply call or write to you and ask you to pay a debt that’s past the statute of limitations. They are allowed to request a voluntary payment.

However, federal law draws a very firm line here. Under the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA), it is absolutely illegal for a collector to sue you or even threaten to sue you over time-barred debt.

Be on the lookout for phrases like “we may be forced to pursue further legal remedies” just as much as an outright threat. If a collector uses that kind of language for a debt you know is too old, they are breaking the law. You may even have a case to sue them.

Facing down aggressive collectors or a lawsuit over an old debt is incredibly stressful, but you don’t have to go through it alone. The law provides real protections for consumers. At Ginsburg Law Group PC, we specialize in debt defense and consumer rights, helping people stand up to illegal collection tactics and secure their financial futures. If you need help figuring out your rights or fighting back, contact us for guidance.