Summary

While Pennsylvania law does not mandate having a will, failing to create one leaves your legacy to the state's rigid intestate succession formulas. Without a designated plan, your spouse may have to split assets with children or estranged relatives, and the court will decide who raises your minor children. A properly executed will allows you to control asset distribution, name trusted guardians, and appoint an executor to streamline the probate process. Probate in Pennsylvania can be time-consuming and costly, especially for assets held solely in your name. Furthermore, the state imposes inheritance taxes ranging from zero percent for spouses to fifteen percent for non-relatives. To ensure a will is valid, it must meet specific signature and witness requirements. Beyond a basic will, comprehensive estate planning should include powers of attorney and healthcare directives to manage incapacity. Regularly updating these documents after major life events, such as marriage or divorce, is essential to prevent unintended consequences and family disputes. Ultimately, a customized estate plan provides peace of mind by ensuring your intentions are honored and your loved ones are protected from unnecessary legal complications.

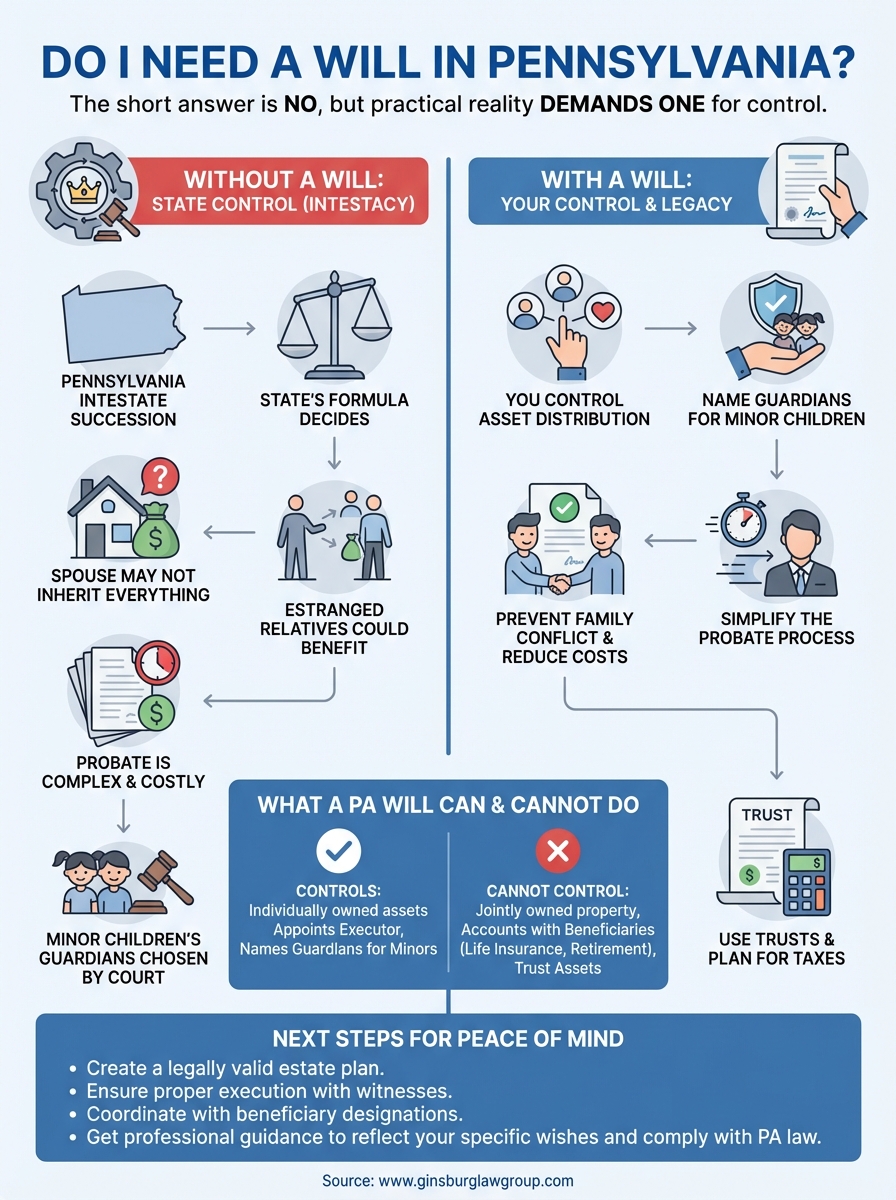

If you’re asking “do I need a will in Pennsylvania,” the short answer is no, Pennsylvania law doesn’t require you to have one. But here’s what matters more: without a will, you lose control over what happens to your assets, your minor children, and even your digital accounts after you pass away.

Pennsylvania’s intestate succession laws will decide who gets what. The state’s formula might not match your wishes at all. Your spouse might not inherit everything. Estranged relatives could receive portions of your estate. And the probate process becomes more complicated, time-consuming, and expensive for the people you leave behind.

At Ginsburg Law Group, we help Pennsylvania residents create wills, trusts, and comprehensive estate plans that actually reflect their intentions. Our estate planning services ensure your assets go where you want them, not where the state decides they should.

This guide breaks down exactly what happens when someone dies without a will in Pennsylvania, how intestate succession works, what probate looks like, and the tax implications you should understand. By the end, you’ll know whether a will makes sense for your situation and what steps to take next.

Why people in Pennsylvania still need a will

Pennsylvania law doesn’t force you to create a will, but practical reality demands one if you care about what happens to your property, your children, and your loved ones after you die. The question “do I need a will in Pennsylvania” becomes less about legal obligation and more about whether you want control over your legacy.

You control exactly who inherits your assets

Without a will, Pennsylvania’s intestate succession statutes determine who receives your property. The state follows a rigid formula that doesn’t account for your relationships, your wishes, or your family dynamics. You might want everything to go to your spouse, but if you have children, your spouse only receives the first $30,000 plus half of the remaining estate. The rest goes to your kids, even if they’re adults who don’t need it and your spouse does.

Your will lets you divide assets however you choose. You can leave specific items to specific people, give more to a child who needs financial help, or exclude someone entirely if you have good reason. Pennsylvania law allows you to disinherit anyone except your spouse (who has a right to claim an elective share). You can donate to charities, create trusts for beneficiaries with special needs, or structure distributions over time instead of giving everything at once.

Pennsylvania’s intestate succession laws don’t consider the quality of your relationships or who actually needs support. They simply follow bloodlines and legal status.

You protect your minor children’s future

Parents with children under 18 face critical decisions that only a will can address properly. When you name a guardian in your will, you designate who will raise your children if both parents die. Without this designation, a Pennsylvania court decides based on what it thinks is best, which might not align with your values or preferences.

The court might choose a relative you wouldn’t trust, or spark a custody battle between family members who each think they should raise your kids. Your will eliminates this uncertainty and gives your children stability during an already traumatic time. You can also name different guardians for different children if age gaps or special needs make that appropriate.

You prevent family conflict and reduce costs

Intestate estates create confusion and resentment among survivors. Family members often disagree about who should administer the estate, who deserves what assets, and how to interpret the deceased person’s wishes. These disputes drag out probate, increase legal costs, and destroy relationships.

Pennsylvania intestacy law sometimes produces counterintuitive results that shock families. If you’re single with no children, your parents inherit everything. If your parents are deceased, your siblings split your estate equally, even if you haven’t spoken to some of them in years. If you have no close relatives, the state searches for distant cousins you might never have met. A will cuts through all this ambiguity with clear instructions that everyone must follow.

You simplify the probate process

A properly drafted will streamlines estate administration in Pennsylvania. You name an executor you trust to handle paperwork, pay debts, and distribute assets. You can waive the bond requirement (saving your estate money) and give your executor broad powers to sell property or manage business interests without repeated court approval.

Without a will, someone must petition to become administrator, which takes longer and costs more. The court might require a bond, which is essentially insurance against mismanagement. Pennsylvania intestacy rules create extra procedural steps that a will eliminates, getting assets to beneficiaries faster and preserving more of your estate’s value.

What a Pennsylvania will can and cannot do

Understanding the boundaries of what a will accomplishes in Pennsylvania helps you set realistic expectations and identify when you need additional estate planning tools. A will serves as your primary instruction document for distributing assets after death, but Pennsylvania law places clear limits on what you can control through this document alone. Some assets automatically bypass your will regardless of what it says, and certain decisions require separate legal instruments to execute properly.

What your will controls in Pennsylvania

Your will governs any property you own in your name alone at the time of death. This includes real estate titled solely to you, bank accounts without beneficiary designations, vehicles, personal belongings, business interests, and investment accounts held individually. You direct exactly who receives these assets and in what proportions.

You also appoint your executor through your will, giving this person legal authority to manage your estate through probate. This includes paying debts, filing tax returns, liquidating assets if necessary, and making final distributions. Pennsylvania allows you to name guardians for minor children, specify whether your executor must post bond, and include instructions for pet care or funeral arrangements.

A Pennsylvania will only controls assets that don’t have another mechanism directing where they go after you die.

What bypasses your will automatically

Jointly owned property transfers directly to the surviving owner regardless of your will’s instructions. If you and your spouse own your house as tenants by the entirety or joint tenants with right of survivorship, your half automatically becomes theirs when you die. Your will can’t redirect it to anyone else.

Bank accounts, retirement plans, and life insurance policies with named beneficiaries skip probate entirely. The financial institution pays directly to whoever you listed on the beneficiary form, even if your will says something different. If you named your brother as your IRA beneficiary in 2015 but your will says everything goes to your sister, your brother gets the IRA.

Assets in a living trust also bypass your will because you already transferred ownership to the trust during your lifetime. Pennsylvania treats trust assets separately from probate property, which is actually an advantage for avoiding delays and maintaining privacy.

What Pennsylvania law restricts

Pennsylvania prevents you from completely disinheriting your spouse through your will. Your spouse can claim an elective share of your estate (typically one-third) even if your will leaves them nothing. You can’t use your will to avoid this right, though a valid prenuptial agreement can.

You also can’t control property indefinitely after death. Pennsylvania’s rule against perpetuities eventually requires trusts to terminate and distribute assets, though recent reforms extended these time limits significantly. When considering whether you need a will in Pennsylvania, recognize that some long-term planning goals require trusts or other structures beyond a basic will.

What happens if you die without a will in Pennsylvania

When you die without a will in Pennsylvania, you die “intestate,” and state law immediately dictates every decision about your estate. Pennsylvania’s intestate succession statutes replace your voice with a rigid legal formula that treats every family identically. The Orphans’ Court supervises the entire process, adding layers of expense and delay that a will could have prevented. Your family gets no choice about who manages your affairs, and beneficiaries receive assets according to bloodline rankings rather than need or your relationship quality.

The state takes control of asset distribution

Pennsylvania’s intestacy laws create a one-size-fits-all inheritance hierarchy that ignores your actual wishes. Your surviving spouse doesn’t automatically inherit everything, even if you assumed they would. If you have children from your current marriage, your spouse receives the first $30,000 plus half of your remaining estate. Your children split the other half equally, regardless of age or financial situation.

The formula becomes more complex with blended families. If you have children from a previous relationship, your current spouse only gets half of your estate, with the other half divided among all your children. Unmarried partners receive nothing under Pennsylvania intestacy law, no matter how long you lived together or how much you contributed to shared assets. Asking yourself “do I need a will in Pennsylvania” becomes crucial when you realize these statutory distributions might completely contradict your intentions.

Pennsylvania intestacy law applies mathematical formulas to human relationships, distributing your life’s work based on legal status rather than love, loyalty, or actual need.

Your estate faces additional complications

Without a will naming an executor, someone must petition the court for letters of administration. Multiple family members might compete for this role, creating conflict and legal fees. Pennsylvania requires administrators to post bond in most cases, which costs money and delays the process. Your administrator has limited powers compared to an executor under a will, requiring repeated court approval for routine transactions like selling property or accessing certain accounts.

Creditors and tax authorities get extended time to file claims against intestate estates. The probate process drags on longer because no one left clear instructions about asset location, account passwords, or business operations. Family members argue about who deserves specific personal items when no written guidance exists, turning grief into bitter disputes over furniture, jewelry, or family photos.

Specific outcomes you lose control over

Intestacy prevents you from leaving anything to friends, charities, or non-relatives who matter to you. Pennsylvania law only recognizes blood relatives and spouses as intestate heirs. If you have no close family, the state searches for distant cousins as remote as great-great-grandparents’ descendants. In rare cases where no relatives exist, your entire estate goes to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania itself rather than causes or people you cared about.

How Pennsylvania intestacy works for common families

Pennsylvania’s intestate succession law applies different formulas depending on your family structure at death. These statutory rules operate automatically when you die without a will, distributing your assets according to rigid categories that might surprise your loved ones. Understanding these scenarios helps you see exactly why the question “do I need a will in Pennsylvania” matters so much for protecting your family’s future.

Married with children from your current marriage

Your surviving spouse receives the first $30,000 of your estate plus half of everything above that amount. Your children from this marriage split the remaining half equally, regardless of their ages or financial needs. If your estate is worth $130,000, your spouse gets $80,000 ($30,000 base plus $50,000 from the remaining $100,000), and your children divide $50,000 among themselves.

This split creates immediate problems for many families. Your spouse might need the house but can’t afford to buy out your children’s share. Your adult children might demand their inheritance immediately while your spouse still needs income to live on. Young children receive their portions at age 18 unless a court appoints a guardian of the estate to manage funds until then, adding more expense and complexity.

Pennsylvania intestacy law forces your surviving spouse to share your estate with your children, creating potential conflicts during the most difficult time in their lives.

Married with children from previous relationships

If you have children from a former marriage or relationship, your current spouse only inherits half of your estate. The other half gets divided equally among all your children, including those from previous partnerships. Pennsylvania makes no distinction between biological children, adopted children, or children from different relationships when calculating intestate shares.

Blended families face particularly harsh outcomes under this formula. Your current spouse receives far less than they would if all children were from your marriage together, potentially leaving them financially vulnerable. Tensions between your spouse and your children from previous relationships often escalate when they must share your estate under court supervision.

Single or widowed with children

Your children inherit everything equally if you have no surviving spouse. Pennsylvania divides your entire estate into equal shares for each child, with deceased children’s portions passing to their own children (your grandchildren) by right of representation. If one of your three children predeceased you but left two kids, your two surviving children each get one-third while your two grandchildren split the remaining third.

No spouse and no children

Your parents inherit your entire estate if you die single with no children. If your parents are both deceased, your siblings split everything equally. Pennsylvania then moves through increasingly distant relatives: nieces and nephews, grandparents, aunts and uncles, and eventually cousins. The state exhausts every possible family connection before claiming your estate.

Pennsylvania probate basics and when it applies

Probate is the legal process where a Pennsylvania court validates your will (if you have one) and supervises the distribution of your estate. Most estates go through some form of probate, but the complexity varies dramatically based on your asset types and total value. Understanding when probate applies helps you see how much time and money your family will spend settling your affairs after you die.

When probate is required in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania requires probate for any asset titled solely in your name without beneficiary designations or joint ownership. Real estate you own individually triggers probate even if your will clearly states who should inherit it. Bank accounts, investment portfolios, and vehicles in your name alone all require court involvement to transfer to your heirs.

Estates exceeding $50,000 typically go through formal probate proceedings in the Orphans’ Court. Smaller estates under this threshold may qualify for simplified procedures that reduce paperwork and costs, but you still need court approval to transfer assets legally. When asking yourself “do i need a will in pennsylvania,” remember that probate happens either way, but your will controls who gets what instead of letting intestacy laws decide.

Assets that skip probate entirely

Several asset types transfer directly to beneficiaries without court involvement. Life insurance policies, retirement accounts, and payable-on-death bank accounts go straight to named beneficiaries through contractual arrangements with financial institutions. Pennsylvania recognizes these designations as superior to will instructions, so updating beneficiary forms matters as much as updating your will.

Property you own jointly with right of survivorship passes automatically to the surviving co-owner. This includes most assets married couples hold together and any accounts or real estate you specifically titled with survivorship language. Transfer-on-death deeds for real estate also bypass probate if Pennsylvania law permits them for your property type.

Proper beneficiary designations and ownership structures can help your family avoid probate delays entirely, but they require careful coordination with your overall estate plan.

The probate process timeline and costs

Pennsylvania probate typically takes six months to two years depending on estate complexity, creditor claims, and family cooperation. Your executor must publish notice to creditors, file inventories with the court, pay valid debts and taxes, and obtain approval before making final distributions. Each step adds time and legal fees that reduce what your beneficiaries ultimately receive.

Expect to pay court filing fees, executor commissions (typically 3-5% of estate value), attorney fees, appraisal costs, and accounting expenses. A $500,000 estate might spend $15,000 to $40,000 on probate costs before heirs receive anything. Contested estates or those requiring property sales multiply these expenses significantly.

What makes a will valid in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania law sets specific requirements that determine whether your will holds up in court after you die. Missing even one element can invalidate your entire document, leaving your estate subject to intestacy rules instead of your stated wishes. Understanding these requirements helps you create a legally enforceable will that actually accomplishes what you intend.

Basic legal requirements you must meet

You must be at least 18 years old to create a valid will in Pennsylvania. The law also requires testamentary capacity, meaning you understand what property you own, who your natural beneficiaries are, and the legal effect of signing a will. Pennsylvania courts presume you have capacity unless someone challenges your mental state with medical evidence or proof of undue influence.

Your will must exist as a written document, either typed or handwritten. Pennsylvania doesn’t recognize oral wills (also called nuncupative wills) except in extremely limited military circumstances. Video recordings of you stating your wishes don’t satisfy the writing requirement. When considering whether you need a will in Pennsylvania, remember that verbal promises to family members carry zero legal weight after you die.

Pennsylvania’s writing requirement exists to prevent fraud and ensure clear evidence of your actual intentions, not what someone claims you said.

Signature and witness rules

You must sign your will personally at the end of the document, or direct someone else to sign for you in your presence if physical disability prevents you from writing. Pennsylvania requires two competent witnesses who watch you sign (or acknowledge your signature) and then sign the will themselves in your presence and each other’s presence.

Your witnesses cannot be beneficiaries under your will, or their spouses. If a witness stands to inherit from your will, Pennsylvania law voids their bequest but keeps the rest of the will valid. This protects against accusations that witnesses influenced you to benefit themselves. Self-proving affidavits signed before a notary make probate easier but aren’t required for validity.

Common mistakes that invalidate wills

Photocopies don’t count as original wills in Pennsylvania. Courts need the actual signed document you executed with witnesses present. Physical alterations after signing, like crossing out names or writing in margins, create questions about validity and might void specific provisions or the entire will.

Duplicate originals signed in separate sessions cause confusion about which version represents your final intent. Pennsylvania law treats each signed copy as potentially revocable by destroying any copy. Creating your will without proper witnesses, using interested parties as witnesses, or failing to sign in their presence all provide grounds for contests that can tie up your estate for years in litigation.

Taxes and costs to plan for in Pennsylvania estates

Pennsylvania imposes costs on estates that many families don’t anticipate until after someone dies. The state charges inheritance tax on most assets passing to beneficiaries, with rates varying based on your relationship to the deceased. Beyond taxes, executor fees, attorney costs, and court charges reduce what your heirs ultimately receive. Understanding these expenses helps you plan strategies to minimize their impact and explains why the question “do I need a will in Pennsylvania” extends beyond just choosing beneficiaries to protecting your estate’s value.

Pennsylvania inheritance tax rates

Pennsylvania inheritance tax applies to the fair market value of your estate on your date of death, calculated separately for each beneficiary based on their relationship to you. Your surviving spouse and minor children pay zero inheritance tax. Adult children and grandchildren pay 4.5% on everything they inherit. Siblings face a 12% tax rate, while all other beneficiaries including friends, unmarried partners, and distant relatives pay 15%.

Transfers to charities, religious organizations, and government entities escape inheritance tax entirely. Life insurance proceeds paid to named beneficiaries also avoid this tax, as do most retirement account distributions. Real estate and business interests get valued at fair market value, which sometimes requires professional appraisals that add more expense to your estate settlement.

Pennsylvania’s inheritance tax hits unmarried partners especially hard, taking 15% of everything they receive while legally married spouses pay nothing at all.

Federal estate tax considerations

The federal estate tax only affects estates exceeding $13.99 million in 2025 (indexed annually for inflation). This threshold means most Pennsylvania families avoid federal estate tax completely. Married couples effectively double this exemption through portability elections, protecting estates up to approximately $28 million from federal taxation.

Assets exceeding these thresholds face a 40% federal tax rate, making advance planning crucial for high-net-value estates. Your executor must file a federal estate tax return within nine months of death if your gross estate surpasses filing thresholds, even if no tax is ultimately due. Gift tax returns filed during your lifetime also affect available federal exemptions.

Probate and administration costs

Executor compensation in Pennsylvania typically runs 3% to 5% of estate value, though executors often waive fees when they’re also beneficiaries. Attorney fees for routine probate administration range from $3,000 to $15,000 depending on complexity, with contested estates or business valuations multiplying these costs dramatically. Court filing fees, publication notices, appraisal expenses, and accounting preparation add thousands more to the total bill.

Estates requiring real estate sales pay broker commissions around 5% to 6% of property value. Maintaining properties during probate adds insurance, utilities, and maintenance costs that drain estate funds monthly. Careful planning reduces these expenses through beneficiary designations, joint ownership structures, and trusts that bypass probate entirely.

Will alternatives and documents to pair with it

A will forms the foundation of your estate plan, but Pennsylvania law recognizes several other tools that work alongside or instead of a traditional will. Some alternatives let you transfer assets without probate entirely, while companion documents protect you during your lifetime when a will offers no help at all. Combining these instruments creates comprehensive protection for both your current needs and your legacy after death.

Revocable living trusts as will alternatives

A revocable living trust lets you transfer property ownership to a trust entity you control while alive, then automatically distributes those assets to beneficiaries after you die without probate. You serve as trustee managing trust property normally, but your successor trustee takes over seamlessly when you pass away or become incapacitated. Pennsylvania courts never get involved with trust assets, keeping your affairs private and avoiding the delays and costs of probate administration.

Trusts cost more to establish than basic wills, typically $2,000 to $4,000 for proper legal drafting. You must actually transfer ownership of accounts and real estate into the trust’s name, which requires new deeds, retitling financial accounts, and updating beneficiary forms. Many people asking “do i need a will in pennsylvania” should consider whether a trust better serves their goals, especially if they own property in multiple states or want to avoid probate entirely.

Beneficiary designations and joint ownership

Retirement accounts, life insurance policies, and payable-on-death bank accounts transfer directly to named beneficiaries without requiring probate or following your will’s instructions. Pennsylvania recognizes transfer-on-death designations for many asset types, letting you specify who inherits specific accounts through simple beneficiary forms. These designations override anything your will says, so you must keep them current as your family situation changes.

Joint ownership with right of survivorship similarly bypasses your will. Property automatically transfers to surviving co-owners when you die, making this arrangement popular for married couples and family homes. Pennsylvania law presumes married couples hold property as tenants by the entirety, which provides this automatic transfer plus creditor protection during your lifetime.

Beneficiary designations and joint ownership eliminate probate delays, but they require careful coordination with your overall estate plan to avoid unintended consequences.

Essential documents to pair with your will

Powers of attorney let you designate someone to manage your finances if you become incapacitated while you’re still alive. Your will offers zero protection during incapacity because it only takes effect after death. Pennsylvania’s durable power of attorney survives mental decline, ensuring someone you trust can pay bills, manage investments, and handle legal matters if you can’t.

Healthcare directives and living wills tell doctors what medical treatments you want or refuse if you can’t communicate. These documents address end-of-life decisions, organ donation, and pain management preferences. Your healthcare power of attorney names someone to make medical choices for you when you’re unable, complementing your financial power of attorney for complete protection.

How to update your will and avoid common mistakes

Your will reflects your life circumstances at the moment you signed it, but Pennsylvania law requires you to update your document when major life events occur. Births, deaths, marriages, divorces, significant asset changes, and moves to different states all create reasons to revise your estate plan. Failing to update your will creates confusion, exposes your estate to legal challenges, and often produces results completely opposite to your current intentions.

When you need to update your Pennsylvania will

Marriage automatically revokes any will you created before the wedding unless your document specifically contemplates your upcoming marriage. Pennsylvania law assumes you intended to provide for your new spouse, giving them an intestate share even if your old will says otherwise. Divorce doesn’t automatically revoke provisions naming your ex-spouse, though it does eliminate them as executor or beneficiary in most cases.

The birth or adoption of children demands immediate will updates. Pennsylvania protects omitted children by giving them intestate shares unless your will clearly shows you intended to exclude them or made alternative provisions outside the will. Moving substantial assets into or out of your estate, selling your home, starting a business, or receiving an inheritance all justify reviewing whether your current will still accomplishes your goals.

Life changes constantly, but your will only protects you if it reflects your current family structure, assets, and wishes.

How to legally revoke or change your will

Pennsylvania recognizes only two methods for changing your will: creating a completely new will that revokes all prior versions, or executing a codicil that amends specific provisions while keeping the rest intact. Both require the same formalities as your original will, including your signature and two witnesses. Never write changes directly on your existing will, cross out names, or add handwritten notes in margins. Courts treat these alterations as potentially invalid and might throw out your entire document.

Physical destruction with intent to revoke also cancels your will in Pennsylvania. Tearing, burning, or shredding your will eliminates it legally if you meant to revoke it, but accidental damage doesn’t count. Creating a new will that explicitly states it revokes all prior wills gives you the cleanest break from old estate plans.

Common mistakes that undermine your estate plan

People often fail to update beneficiary designations on retirement accounts and life insurance policies after creating new wills. These beneficiary forms control who inherits those assets, overriding anything your will says. Naming minors directly as beneficiaries creates guardianship complications instead of using trusts to manage assets until they mature.

Choosing executors who can’t serve because they live out of state, have health problems, or lack financial skills creates unnecessary probate delays. Pennsylvania law requires executors to post bond unless your will waives this requirement, so including this waiver saves your estate money. When reconsidering “do i need a will in pennsylvania” after major life changes, remember that outdated estate plans cause more problems than having no plan at all.

Next steps for peace of mind

You now understand how Pennsylvania handles estates with and without wills, what probate involves, and the specific costs your family faces after you die. The question “do i need a will in pennsylvania” has a clear answer: you need one if you want control over who inherits your assets, who raises your children, and who manages your estate. Pennsylvania’s intestacy laws work against most families, splitting assets in ways that create financial hardship and family conflict.

Creating a legally valid will requires more than downloading a template online. You need proper execution with witnesses, accurate property descriptions, and coordination with beneficiary designations on retirement accounts and life insurance. Small mistakes invalidate entire documents, leaving your family with the exact intestate distribution you tried to avoid.

Schedule a free consultation with Ginsburg Law Group to create an estate plan that actually protects your family. We draft wills, trusts, and powers of attorney that reflect your specific wishes and comply with Pennsylvania law.