Most people know they need some kind of estate plan, but figuring out which tools to use can feel overwhelming. Understanding the difference between will and trust is one of the most common questions clients bring to our estate planning team at Ginsburg Law Group. The answer isn’t always straightforward, and getting it wrong can create real problems for the people you’re trying to protect.

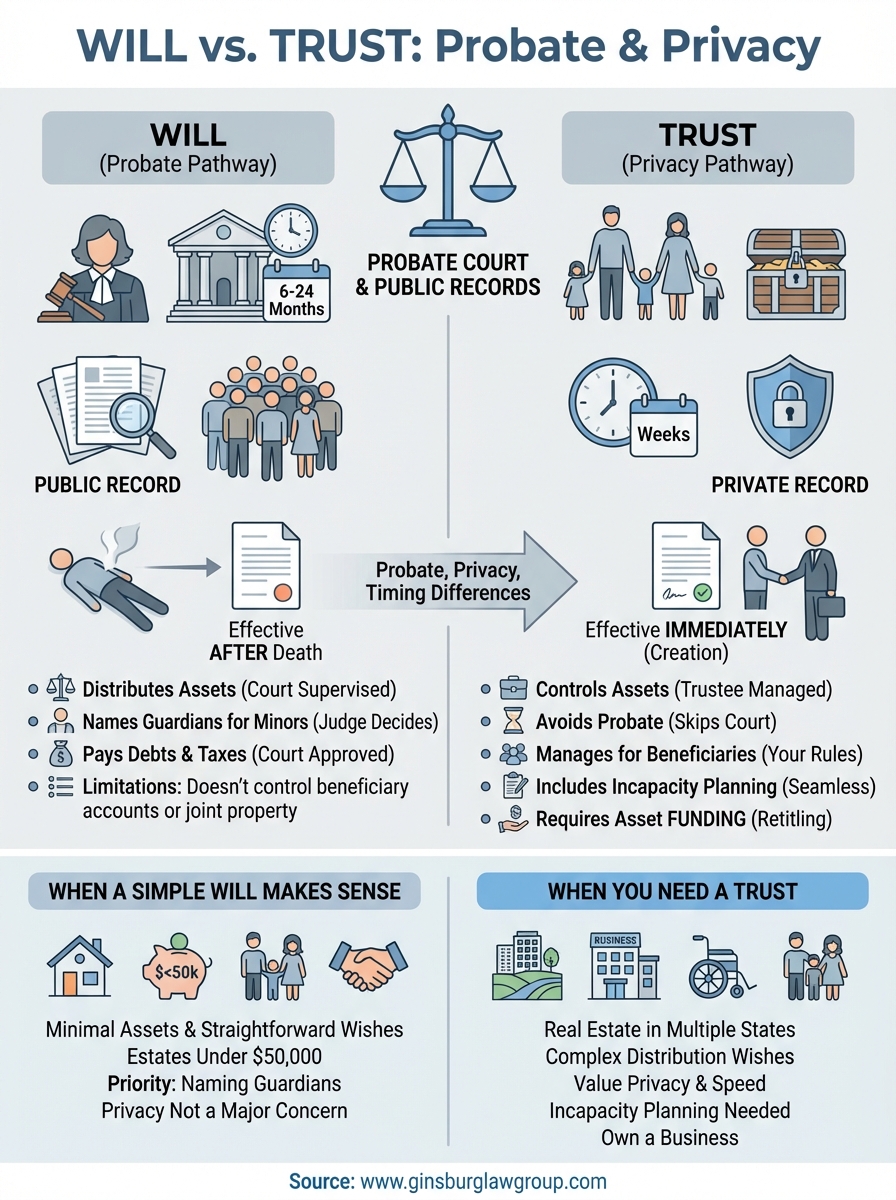

Both documents help you control what happens to your assets after you’re gone. But they work in fundamentally different ways, especially when it comes to probate court, privacy, and timing. A will only takes effect after death and typically requires court involvement. A trust can work during your lifetime, skip probate entirely, and keep your affairs out of public records.

This guide breaks down the practical differences between wills and trusts so you can make an informed decision. We’ll cover how each handles probate, what level of privacy you can expect, and the situations where one option clearly beats the other. By the end, you’ll know whether a will, a trust, or both makes sense for protecting your family and assets.

What a will is and what it can do

A will is a legal document that tells the court how you want your property distributed after you die. You name a personal representative (sometimes called an executor) who handles your estate, pays your debts, and distributes assets according to your instructions. The will only becomes active after your death, and it must go through probate court before anyone receives anything.

The core function of a will

Your will serves as instructions to the probate court about who gets what from your estate. You can name guardians for minor children, specify which family members or friends receive certain assets, and outline how you want debts and taxes handled. The court reviews your will, validates it, and supervises the distribution process to ensure everything follows your wishes and state law.

A will gives you control over your legacy, but the probate court must approve every action your executor takes before assets change hands.

Most people use wills to handle straightforward estates where probate costs and timeline aren’t major concerns. If you own property in your name alone, have bank accounts without beneficiaries, or possess personal items with sentimental value, your will directs where these go. You can also use it to forgive debts owed to you or make specific gifts to charities.

Assets and beneficiaries you can control

You control the distribution of any asset titled in your name that doesn’t have a beneficiary designation. This includes your house (if owned solely), vehicles, jewelry, furniture, and personal belongings. You can also direct who inherits bank accounts that don’t name a payable-on-death beneficiary and investment accounts without transfer-on-death designations.

Naming guardians for underage children is one of the most critical functions of a will. Without this designation, a judge decides who raises your kids based on state guidelines rather than your preferences. You can name both primary and backup guardians to ensure your children end up with people you trust.

Limitations you need to know about

Wills don’t control everything you own. Retirement accounts, life insurance policies, and any assets with beneficiary designations pass directly to the named beneficiaries outside of probate. Property you own jointly with right of survivorship automatically transfers to the surviving owner, regardless of what your will says. Understanding the difference between will and trust becomes important here because these limitations don’t apply to trusts in the same way.

What a trust is and how it works

A trust is a legal arrangement where you transfer ownership of your assets to a separate entity that holds them for the benefit of people you name. Unlike a will, a trust can take effect immediately when you create it, not just after you die. You appoint a trustee (often yourself initially) who manages the assets according to the rules you set in the trust document. This structure lets you control how and when your beneficiaries receive their inheritance while avoiding probate court entirely.

How trusts operate during your lifetime

Most people use revocable living trusts that they can change or cancel anytime while alive. You typically serve as your own trustee, managing assets the same way you always have, but the trust technically owns them. When you die, a successor trustee you named takes over and distributes assets directly to beneficiaries without court involvement. This immediate transfer is a key part of the difference between will and trust structures.

A properly funded trust skips probate completely, allowing your beneficiaries to receive assets within weeks instead of months or years.

The trust only works for assets you actually transfer into it. You must change titles on real estate, retitle bank accounts, and move investment holdings into the trust’s name. Many people create trusts but forget this funding step, which means those assets still end up in probate despite having a trust in place.

The trustee’s role and responsibilities

Your trustee manages trust assets according to your written instructions and state law. They pay bills, file taxes, handle investments, and eventually distribute assets to beneficiaries. You can name yourself as initial trustee, a family member, or a professional trustee service depending on your situation and comfort level with financial management.

Key differences: probate, privacy, and timing

The most significant difference between will and trust comes down to three factors: probate requirements, privacy protection, and when control begins. These distinctions directly affect how quickly your beneficiaries receive assets, who can see your financial information, and whether you maintain control during your lifetime. Understanding these differences helps you choose the right tool for your specific situation.

Probate process comparison

Wills must go through probate court, which typically takes six months to two years depending on your state and estate complexity. Your executor files the will, notifies creditors, pays debts and taxes, and eventually distributes assets under court supervision. Probate costs include court fees, attorney fees, and executor compensation, often totaling 3-7% of your estate value.

Trusts skip probate entirely because you technically don’t own the assets anymore when you die. Your successor trustee distributes assets directly to beneficiaries within weeks instead of months. This saves both time and money while giving your family immediate access to resources they need.

Avoiding probate through a trust can save your family thousands of dollars and months of waiting while maintaining complete control of your assets during your lifetime.

Privacy and public records

Probate makes your will a public document that anyone can read at the courthouse. Nosy neighbors, disgruntled relatives, and scam artists can see exactly what you owned and who inherited it. Trusts remain completely private because they never enter the court system. Only your trustee and beneficiaries know what the trust contains or how assets get distributed.

When control takes effect

Wills only activate after your death, offering no protection if you become incapacitated. Trusts work immediately after creation and include instructions for managing your affairs if you can’t do it yourself.

Which option fits your situation

Choosing between a will and trust depends on your asset types, family situation, and how much you value privacy and speed. The difference between will and trust becomes most clear when you look at your specific circumstances rather than general advice. Your decision should account for what you own, who you’re protecting, and how quickly you want beneficiaries to access assets after your death.

When a simple will makes sense

You probably only need a will if you own minimal assets, have straightforward wishes, and don’t mind probate court. This works well for young people just starting out, those with estates under $50,000, or anyone whose main concern is naming guardians for minor children. Probate costs matter less when your estate is small, and the public nature of wills isn’t a concern if you have nothing to hide.

A will provides adequate protection for simple estates where avoiding probate costs less than setting up and funding a trust.

When you need a trust instead

You benefit from a trust when you own real estate in multiple states, want to avoid probate delays, or value keeping your financial affairs private. Trusts make sense if you have a blended family with complex distribution wishes, own a business that needs seamless transition, or want to protect assets from creditors. You should also consider a trust if you’re concerned about becoming incapacitated and need someone to manage your affairs without court involvement.

How to set up a will or trust the right way

Setting up a will or trust correctly requires careful planning and proper execution to ensure your documents hold up in court. You can technically create either document yourself, but mistakes in wording or execution requirements can invalidate the entire thing. Most states require specific witness signatures, notarization, or both depending on whether you choose a will or trust. The difference between will and trust setup processes varies significantly, with trusts demanding more upfront work but providing better long-term protection.

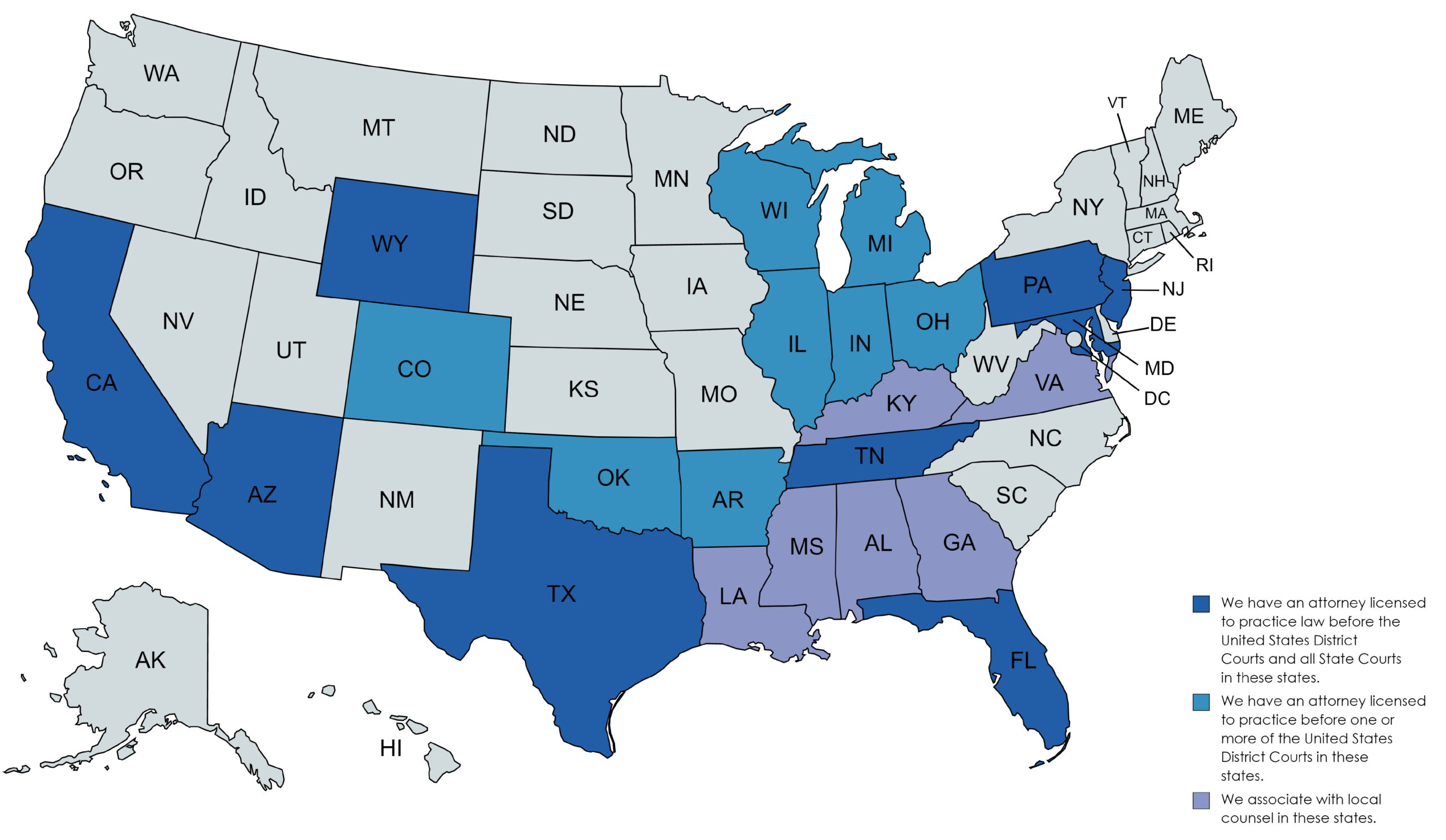

Finding the right legal help

You should work with an estate planning attorney who knows your state’s laws and can draft documents that match your specific situation. Online forms and templates miss important details about your family structure, asset types, and state requirements that could create problems later. A qualified attorney ensures your will gets witnessed properly or your trust includes all necessary funding instructions to actually work when you need it.

Working with an experienced attorney costs more initially but prevents expensive court battles and family disputes after you’re gone.

What documents and information you need

Gather a complete list of your assets including bank accounts, real estate deeds, investment statements, and insurance policies before meeting with an attorney. You’ll need full legal names and contact information for everyone you want to name as beneficiaries, executors, trustees, or guardians. Bring documentation showing how you currently own each asset (sole ownership, joint tenancy, etc.) so your attorney can recommend the best approach for transferring or protecting each one.

Next steps to protect your family

You now understand the difference between will and trust and how each protects your family in different ways. The next step is deciding which option fits your situation and getting the documents created properly. Waiting to set up your estate plan puts your family at risk of court battles, financial delays, and unnecessary expenses if something happens to you unexpectedly.

Start by making a complete list of everything you own and who you want to inherit each asset. Think about whether you value privacy enough to justify the upfront cost of a trust or if a simple will meets your needs. Consider your family dynamics, how you currently hold title to property, and whether avoiding probate matters enough to do the extra work of funding a trust.

Contact Ginsburg Law Group for a free consultation where we can review your specific situation and recommend the right estate planning approach. We’ll help you understand exactly what documents you need and guide you through the entire process of protecting your family.